Made by Tomáš Libertíny —and Bees

The Slovakian artist is presenting Chronosophia, a solo show with pieces built out of honeycombs, at Brussels’ Spazio Nobile

It’s no coincidence Tomáš Libertíny named his most recent solo show Chronosophia: the artist is quite aware of his obsession with time. That element helped him conceive a series of intricate and delicate tributes to the ephemerality and beauty of an everyday item like the honeycomb –one that might also disappear due to colony collapse disorder.

Now, those interested in visiting Chronosophia should also be aware of time: the exhibition, part of the programme of the Brussels Gallery Weekend, closes this September 17 at Spazio Nobile.

In a recent conversation with the Slovakian creator we discussed two new additions to the show —the red version of his Honeycomb Vase and the large Endless Column—, how 3D printing is like a Roman amphitheater and the origins of his penchant for “mundane” materials such as beeswax.

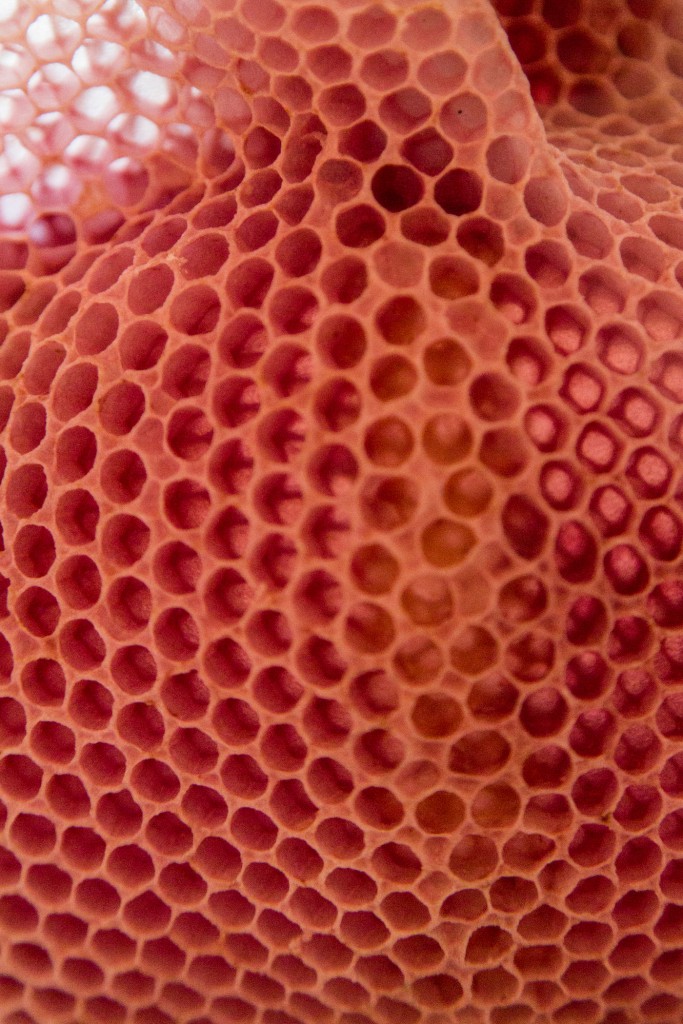

TLmag: On a semi-serious note: Has anyone complained about the Red Honeycomb Vase triggering their trypophobia?

Tomáš Libertíny: The test group has reported zero complaints or any side effects related to the trypophobia; the only byproduct of the experience is pure awe.

Jokes aside, indeed the beauty of natural honeycomb made by honeybees lies in its inconsistencies. Just like ours, the life of a bee is not an isolated activity, but one a subject to plethora of variables. These variations make life so richly diverse. A honeycomb pattern

made by a computer, as a result of an algorithm, and a honeycomb pattern made by bees are two different experiences. Regarding trypophobia, I assume there are many people who could feel repulsed by wild organic structures, but this sensation doesn’t mean one has a medical condition of a phobia. I think bees are one of the few insects that have a positive connotation both aesthetically as well as practically. That is the reason it has been, and still is, so popular as a symbol both in heraldic and graphic works.

TLmag: Were there any technical progressions in the dye technique between your Unbearable Lightness and the Red Vase?

TL: Bees have a shifted visible spectrum toward the ultraviolet, and thus they have lower sensitivity to the wavelengths between 620 to 750 nm. This is the range which we basically refer to as shades of red. Psychology attributes the colour red to life, danger and energy, which I thought was a fascinating contradiction and paradox —as well as a surprise fact.

Theoretically speaking, bees do not pollinate red coloured flowers. Hence, regarding my own work, this “blindness” is the key metaphor in the choice to manipulate the making of the honeycomb with natural red pigments. In addition, Roman soldiers wore red tunics, since the red was a colour of war. In Russian language, the word for red is krasniy, which literally means beautiful. Most obvious reference would the blood of Christ as is referred to by the Roman Catholic Church.

TLmag: These pieces speak of ephemerality. Given the material, are you also talking about the ephemeral regarding our willingly blissful

ignorance of the near future of the global honeybee population?

TL: You are right, the works speak of ephemerality. However, my obsession with ephemerality was related more to the idea of passage of time, the tragedy employing catharsis, the non-existence of return (einmal-ist-keinmal by Nietzsche), instability and life in general, hence very philosophical.

The “made by bees” project has however acquired new meaning in the light of the news about the disappearance of bees, with the colony collapse disorder. When I started working with the idea in 2005, this wasn’t yet a major headline. Now we know that the main culprit behind the tragic losses in numbers of bees is the abusive employment of pesticides. Everything is interconnected. We are all part of the same ecosystem. The “made by bees” project helps to create a certain empathy and awareness in this context. I hope it will continue to do so.

TLmag: There is something, indeed, very visually Brancusian about your Endless Column. What’s behind it conceptually?

TL: It is a conceptual milkshake of the biblical tower of Babylon and that of the Camus’s Myth of Sisyphus: the force of ambition that one has to have in order to achieve greatness versus the inevitable force of fate that one has to accept to be free. There is also a nice dialects between the work being never finished versus work being perfect already in every stage.

It is true: the Endless Column is very much a tribute to Constantin Brancusi. He staged his sculptures —that is, pedestals on another pedestal. The famous outdoor memorial column of the same name at Târgu Jiu, built in 1938, symbolises infinite sacrifice, but it is

also built of geometric elements with half elements on top.

The idea of sacrifice is very dear to me. You could look at the continuity of life as a form of sacrifice. My Endless Column is a memorial to that kind of unawareness of sacrifice, where we live life to give life without asking back. We fulfil a task without ever being officially employed —I guess we are hired when we are born.

TLmag: Beekeeping is quite a structured activity in the Netherlands, with nearly 80,000 hives in the country. Do you work with the bees in Rotterdam, where you have your studio? If so, how have the local regulations impacted your practice?

TL: I never kept my own bees. It was a conscious decision. I have learned much more from collaborating with beekeepers than I would keeping bees myself. There is a couple of them in Rotterdam that I’ve work with for some time now, on and off, but I am in touch with several beekeepers around the whole of the Netherlands.

Beekeepers are the best people, kind and generous, nerdy and empathetic. I have never met a beekeeper who was a derrière.

TLmag: With the objects in Chronosophia you’re proposing the opposite of 3D printing: let’s not have it right now, let’s instead relinquish control. Was is your rationale behind that proposal?

TL: 3D printing is a manufacturing method: it allows for variety and complexity in contrast to the traditional automated production line. I am throwing and idea out there to imagine a world where you outsource the “making” to natural processes —or at least parts of it. The only way to do this is by thorough understanding of the inner workings. Harnessing energy from the sun is the best example: What if instead of creating artificial surfaces we plug in the trees and create this hybrid system of natural solar panel, converting chemical reaction into a small amount of energy? I love the example of the difference between the Greek and the Roman construction of amphitheater. The Greek one was created in a natural context, using the topography of the place and building only the seats and the stage. The Roman one was built in the middle of the city, replicating the acoustic and dramatic condition of a half circular valley.

TLmag: The thing I remember the most about visiting Slovakia is that, no matter how urban the location, nature was never far away –either some Carpathian landscape or a national park. Do you think growing up there has anything to do with the work you’re currently doing?

TL: Certainly, Slovakia is less populated then most of the Western countries. You have the privilege of getting lost in nature. Of course, there are many places like this elsewhere… but nevertheless, my upbringing certainly made an impact on my appreciation of nature and “being” in nature. I am still in awe by its grand visual and physical power. You have to have a certain respect towards nature. Growing up in cities wires our brain in a different way: we live in a time of anxiety propelled by media and mediation. That is why I work with seemingly mundane materials such as beeswax, paper or BiC ink.