Artists and African Textiles – the Use and Meaning of Textiles in Contemporary African Art

Textiles across the African continent are produced using a wide spectrum of materials and techniques, from the painstaking embroidery of a dress or gown to the machine-printed products of integrated textile mills. Artists of African heritage have long understood that textiles today (and in the past) are often of much greater significance and far more widely produced than the superb African sculptural traditions admired by the West.

African taste and patronage has also directed the global textile industry for many centuries. Yinka Shonibare MBE celebrates the international, hybrid nature of the ‘African prints’ which are his signature medium and which, although hugely popular in Africa, originated in the failed Dutch attempt of the early 1800s to imitate traditional Javanese batiks through machine-manufactured wax prints.

NORTH AFRICA

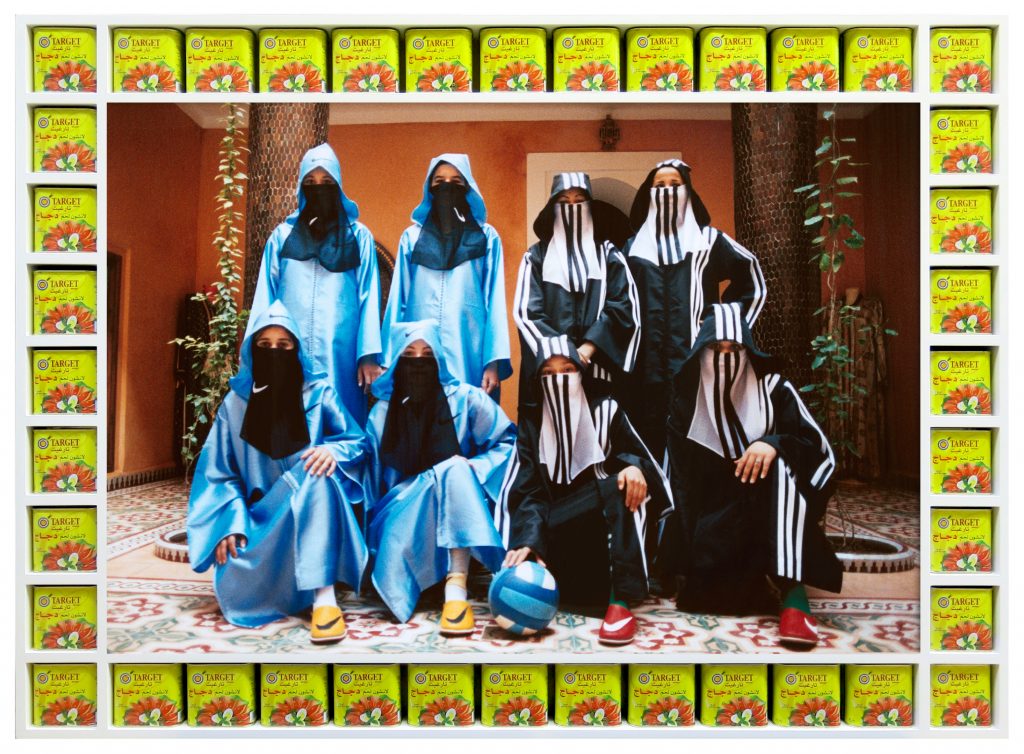

Rachid Koraïchi respectfully adds his own creations to the lexicon of signs and symbols which appear in the woven or embroidered textiles of the Maghreb, while Hassan Hajjaj subverts the West’s ‘orientalist’ obsession with veiling, championing the football-playing and motorbike-riding henna girls of Marrakesh.

WEST AFRICA

A recurring theme in the work of Owusu-Ankomah is the adinkra system of signs and symbols originating from the Akan pre-colonial cloth printing tradition in Ghana, each sign relating to a particular proverb or saying. Abdoulaye Konaté pays tribute to the Mandé hunters of Mali in many of his large textile hangings, in particular their tunics which are covered with multiple protective charms. Peju Alatise has always used textiles in her work, from the wax prints known as Ankara, to the white cotton sheeting which may be the base for masquerade costumes or for the Yoruba resist-dyed cloths known as adire. She celebrates womanhood by suggesting how the female form turns cloth into sculpture. Atta Kwami subtly references Asante narrow-strip kente cloth and other art forms from the city of Kumasi, while Nnenna Okore explores her Igbo heritage in a series of works in which she uses clay and burlap to suggest the costumes worn during the Mmmo or Maiden Spirit masquerade.

EASTERN AFRICA

Contemporary artists re-interpret (and become part of) the factory-printed and woven traditions of eastern and southern Africa with their global history of production. Evans Mbugua and Lawrence Lemaona highlight the kanga tradition of Tanzania and Kenya, in particular its extraordinary ability to allow women to communicate a range of messages, thoughts, fears and emotions through a combination of pattern and the KiSwahili inscription carried by each individual pair of textiles. A very different fabric is the Ugandan cloth, made from the bark of a species of fig tree,

which José Hendo uses in her exquisite high fashion creations.

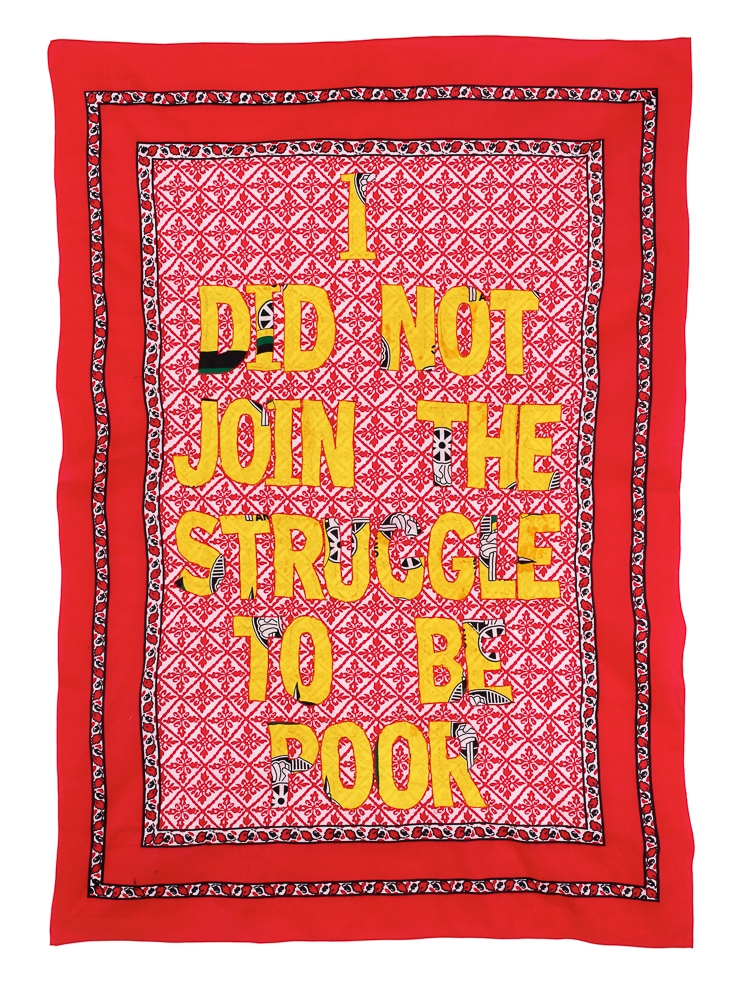

CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN AFRICA

Eddie Kamuanga Ilunga employs a striking juxtaposition of richly coloured and sensuous printed fabrics which envelop the highly stylised figures of Mangbetu people, their bodies outlined with computer circuitry, a reference both to the DRC’s export of coltan, integral to the manufacture of computers and mobiles, and to the threat which modern technology in general poses to the traditional way of life of the Mangbetu. Ann Gollifer draws attention to the many languages spoken in Mozambique through the printed textiles known as capulana worn by Makonde and by other Mozambican women, while Mary Sibande clothes her alter ego ‘Sophie’ in sumptuous blue material which suggests the Blaudruck or blue print originally worn by German and Swiss settlers at the Cape. Today this cloth is widely worn in South Africa under the name isishweshwe, after the nineteenth century Sotho king Moshoeshoe. He decreed that this cloth, together with woollen blankets originally manufactured in Scotland, should be worn by his Sotho people. Both textiles are now produced in South Africa, and the blankets were famously depicted by the artist-photographer Araminta de Clermont.